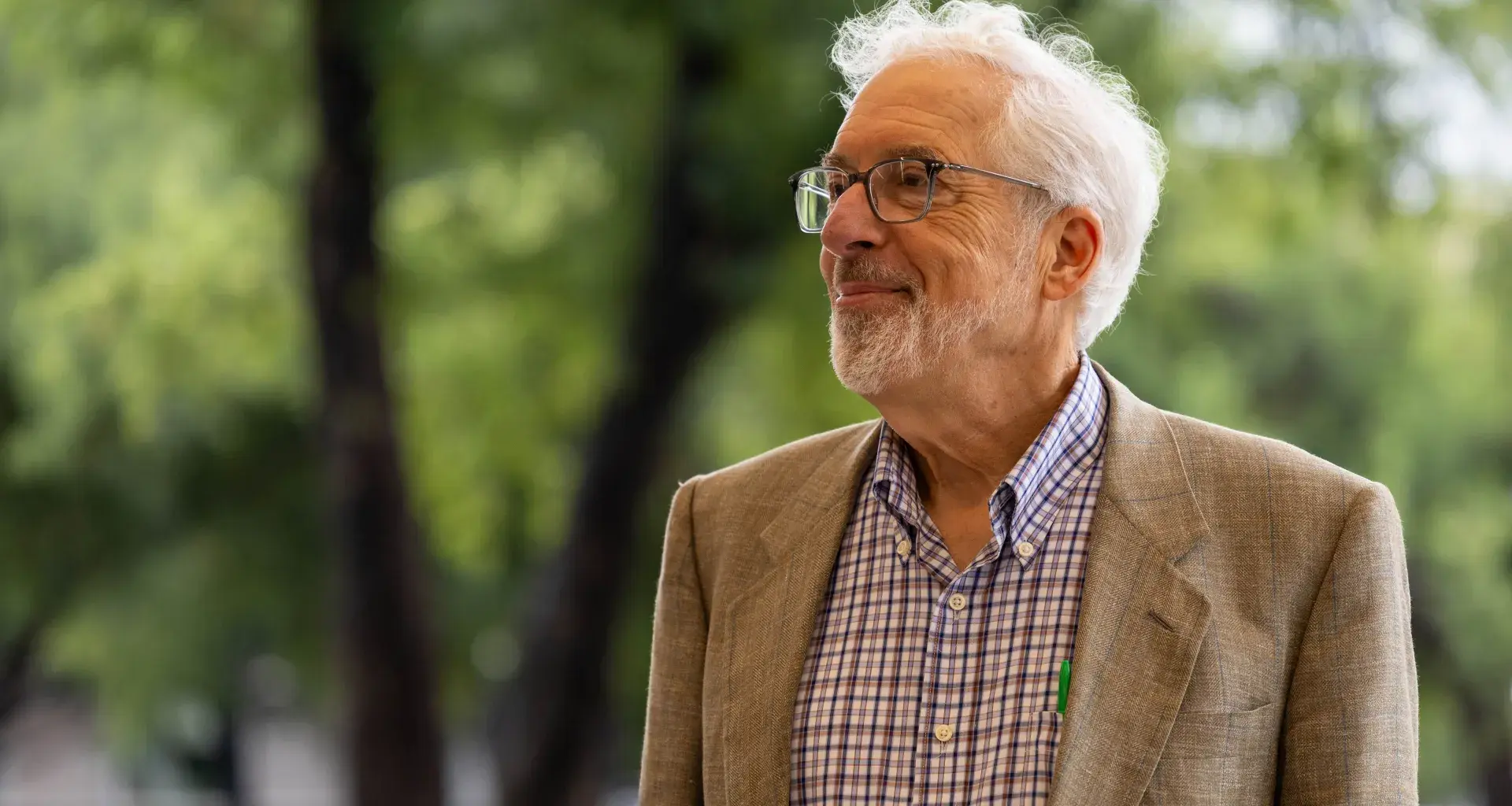

Dr. Steven Popper doesn’t get invited to many parties. At least, that’s a quip he makes when asked to describe his career.

“It’s all pretty boring, which is why people don’t come up to me at parties,” he laughs.

However, this apparent dullness contrasts with a career that has taken him from the depths of a nuclear command bunker in Omaha to the top floors of the Ministry of Science and Technology in Beijing.

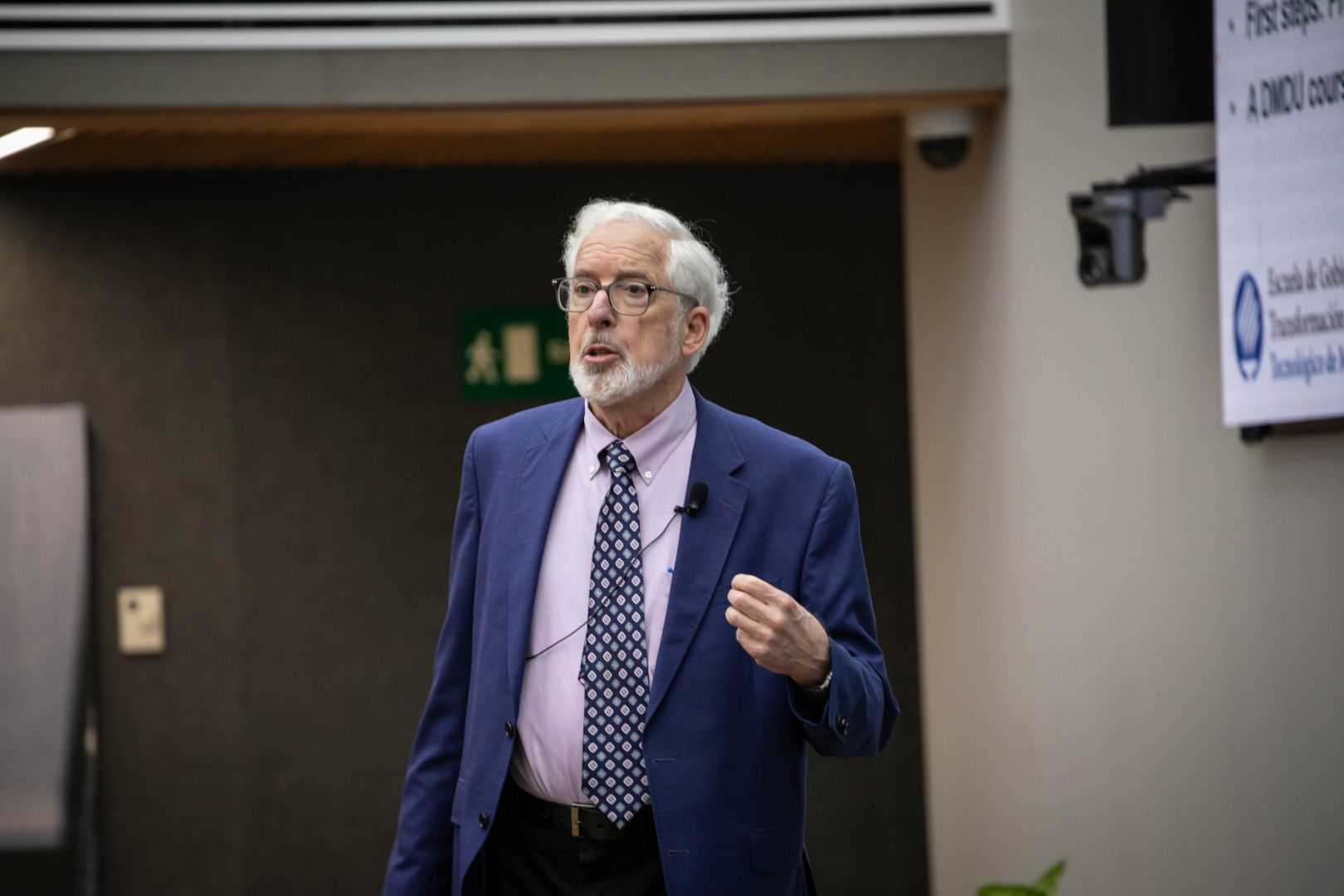

Having spent decades in full-time employment at the RAND Corporation, Popper currently serves as a distinguished professor of decision science at Tecnológico de Monterrey’s School of Social Sciences and Government.

The technical name of the field he pioneered in the 1990s is “decision-making under deep uncertainty.” This field has become more relevant due to events ranging from climate change to technological disruption and global pandemics.

The unlikely economist

Popper is a member of the Faculty of Excellence, a Tec de Monterrey initiative to appoint internationally renowned professors of the highest level to its academic programs.

He had to break down the barriers between academic disciplines to become what he calls an “instrument builder”: someone who creates tools for decision-makers to navigate uncertainty.

Popper earned a bachelor’s degree in Biophysical Chemistry and took courses in Modern European History and Comparative Literature before economics appeared on his radar.

Recalling his university years, he says, “I used to think economics was all about money.” “It wasn’t much in fashion back in the day.”

It was during his sabbatical year at Berkeley (having followed a girlfriend to law school) that Popper discovered his calling.

Armed with nothing but a backpack and a portable typewriter, he began visiting Nobel laureates during their office hours to ask them about their work and discuss ideas that were unfamiliar to him.

“I discovered to my horror that the people who seemed to be talking about things I was fundamentally interested in were economists,” he says.

“I discovered to my horror that the people who seemed to be talking about things I was fundamentally interested in were economists.”

But the economics that attracted Popper was not the theoretical and mathematical discipline that held sway in academia.

He was interested in two phenomena: the dynamics of technological change at the micro level and the transformation of economic systems at the macro level.

The traditional economics he encountered focused on “comparative statics,” which compared one equilibrium with another without examining the dynamic path between them.

In general, economics doesn’t deal with dynamics,” he explains. “There was no discussion of the dynamic path from one equilibrium to another.”

This fundamental disconnect between economic theory and real-world change would shape his entire career.

Having received his Ph.D. from Berkeley, Popper made what many considered to be a risky career decision.

Instead of following a traditional academic path, he joined the RAND Corporation in 1986, initially as a specialist in the economics of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

RAND is a nonprofit institution that develops innovative solutions to public policy challenges and problems related to decision-making.

“On any given day or specific project, I could reach into any of a variety of toolkits: that of the economist, the psychologist, the social scientist, or the physical scientist.”

But RAND turned out to be the perfect environment for Popper’s interdisciplinary approach.

The organization’s structure enabled him to move fluidly between different policy areas and methodologies.

“On any given day or specific project, I could reach into any of a variety of toolkits: that of the economist, the psychologist, the social scientist, or the physical scientist,” he explains.

Popper used many of these tools during the decades he spent at RAND.

He worked on domestic science and technology policy and served as associate director of the Science and Technology Policy Institute (an advisory body to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy).

He also led projects around the world from China and South Korea to Mexico and Israel.

His work contributed to significant policy decisions, including the release of GPS for civilian use and early frameworks for internet governance.

The Deep Uncertainty Revolution

Perhaps Popper’s most significant contribution has been his work on decision-making under deep uncertainty, a field he developed with his RAND colleagues in the early 1990s.

The concept distinguishes between regular uncertainty where we can assign likelihoods to different outcomes and deep uncertainty where we cannot.

“We make all kinds of decisions under uncertainty all the time,” Popper explains, citing everyday examples like taking flights or calling an Uber. “But when it comes to collective and public decisions, it becomes much more difficult.”

The 9/11 attacks provided an example of profound uncertainty.

In the aftermath, policymakers had to make crucial decisions concerning how to prevent future attacks without knowing the actual likelihood of such events occurring.

“Was it ten percent? Fifty percent? Almost certain? Inability to assign meaningful probabilities made traditional risk assessment impossible.”

Initially, it was a tough sell.

“The response we would get was, ‘Guys, this is truly fascinating.’ I don’t know how I managed to explain it to my colleagues,” Popper recalls.

But now, after a series of global crises such as the bursting of the dotcom bubble, the 9/11 attacks, the financial crisis, Brexit, COVID-19, and various geopolitical upheavals, they became much more receptive.

“I no longer find it hard to explain,” he says. “People now say, ‘Yes, this is really something we’ve had first-hand experience of! Tell us more.’”

Popper’s approach represents a fundamental departure from the traditional “predict-then-act” model that pervades so much policy design.

Instead of trying to make more accurate predictions, he advocates asking a different question: “How should I conceive my short-term initiatives to make them consistent with my long-term goals across a wide range of possible futures?”

This approach moves away from optimization and towards what he calls “hedge positions,” which are strategies that perform reasonably well across multiple scenarios as opposed to perfectly in a predicted future.

It is a shift from deductive to inductive reasoning, from looking for the single “best” answer to exploring “what if” scenarios.

The method has been applied across a variety of fields from urban planning to homeland security.

Mexico and the future of decision-making

Now based in Mexico City, Popper sees a country that has to cope with a fundamental challenge reflecting the problems experienced by world democracies:

“How is Mexico going to make decisions?” The diffusion of authority across multiple levels of government, combined with increasingly complex, interconnected problems, has created what he refers to as “diffusion of responsibility.”

His work on housing affordability in Monterrey is a good example of this.

The problem impacts sixteen different municipal governments and millions of people, and there is no regional body to coordinate responses.

He argues that traditional government structures are inadequate to address such complex, multi-jurisdictional challenges.

“Mexico has developed to the point where it has to take the next step,” he suggests.

“And it really has to think about how to address the housing issue here in Monterrey and poverty in Mexico City.”

Despite his experience in the uncertainty field, Popper readily admits that his professional skills have not made him any less anxious on a personal level.

“I think it’s more an age thing,” he replies when asked if his job has helped him deal with life’s uncertainties.

“I’m basically an instrument builder.”

As Popper settles into his role at the Tec, his work continues to evolve.

The deep uncertainty field, once dismissed as too abstract for practical application, has become increasingly relevant as organizations grapple with unprecedented challenges.

From corporate planning in an era of supply chain disruption to government responses to climate change, the tools and approaches Popper helped develop are finding new applications.

“I’m basically an instrument builder,” he reflects.

“I build tools that enable decision-makers, planners and the public to observe phenomena that are otherwise difficult to perceive, and to deal with uncertainty about the future in a sophisticated way.”

His professional path shows the kind of intellectual agility that may become increasingly necessary in an uncertain world.

By refusing to be constrained by traditional disciplinary boundaries, Popper has created tools that help others navigate complexity and uncertainty.

ALSO READ: