“Mexico has narrowed many gaps in education, health, and urbanization, but not the technological gap that defines our future,” warned Ricardo Hausmann, Director of Harvard’s Growth Lab.

Hausmann gave the keynote speech at Tec de Monterrey on the 70th anniversary of its Bachelor’s Degree in Economics (Spanish acronym LEC).

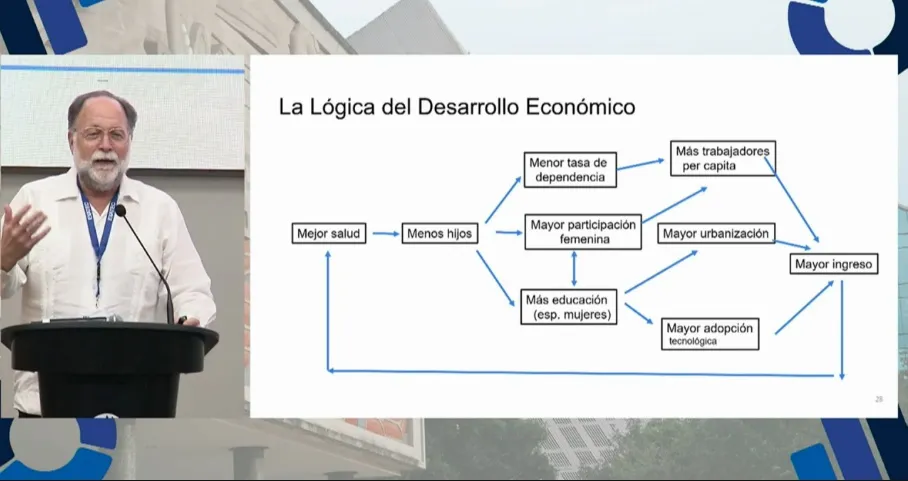

The Venezuelan economist pointed out that even though the region has managed to reduce differences in life expectancy, fertility, schooling, the number of working women, and urbanization, per capita income has yet to reach that of the most developed countries.

“If all social and capital factors converge, GDP per capita should too. But that is not the case,” explained Hausmann.

Hausmann highlighted that our country has made progress in areas like life expectancy (rising from 80% of U.S. life expectancy in 1960 to the current level of 95%) and fertility (which has a rate comparable to that of the U.S.).

Moreover, in regard to education and capital, gaps have been narrowed in both schooling and university enrollment and demographics and employment, as well as the rising number of working women, urbanization, and workers per capita.

Despite these advances, Mexico has to deal with a widening technological gap.

Hausmann pointed out that Mexico was four times richer than South Korea in 1960, whereas today South Korea is three times richer than Mexico.

While Mexico spends only 0.3% of GDP on R&D (Research and Development), South Korea invests 4.8%. Mexico generates barely 1% of the patents registered by the United States, while South Korea produces 250 times more.

The Asian country achieved this despite currently having fewer university students than Mexico, which demonstrates that innovation can precede education of the masses.

These data show that although Mexico has narrowed social and educational gaps, the challenge is now to ramp up technological innovation to catch up with world leaders.

“Consequently, Mexicans drive Kias made in Pesquería, right here in Nuevo Leon, and use Samsung appliances made in Querétaro and Tijuana,” he said ironically.

The “black box” of innovation

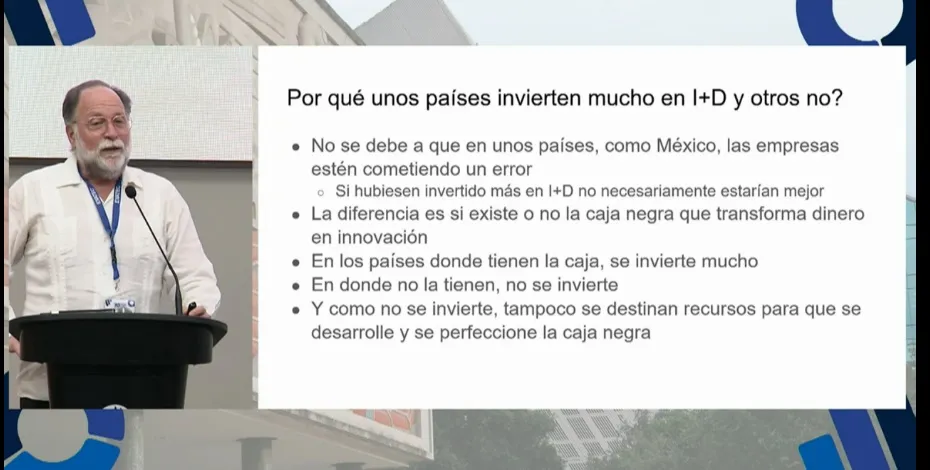

Hausmann explained that the low level of private investment in R&D is not down to a lack of talent but because companies see this expenditure as a “black hole” into which money disappears without producing results.

The difference between countries that invest successfully and those that don’t lies in having a “black box”: a system that turns investment into innovation. When companies see a black box, they invest; if they throw money into a black hole, they lose it.

If Mexico were to allocate 4.8% of GDP to R&D, as South Korea does, it would not necessarily get better results because innovation infrastructure does not turn resources into results.

This also limits research: Mexico has twenty-six times fewer researchers than Korea, most of whom work in the public sector, which is the main source of funding.

Hausmann proposed transforming “fundamentally teaching” universities into productive innovation centers with direct funding from companies trying to solve real problems.

This is where the “chicken and egg problem” comes into play: companies need researchers to apply for patents and create products, and universities need funding from companies.

“We need universities to be black boxes of knowledge that come up with solutions to real problems,” Hausmann said. Most twentieth-century innovation was developed in corporate labs like AT&T’s Bell Labs, not in startups.

Artificial intelligence as an accelerant

Hausmann said that artificial intelligence could accelerate the accumulation of knowledge, which might otherwise take years.

“Although AI is great at answering questions, humans are still needed to ask them and set goals. If you do better with ChatGPT than without it, don’t be afraid of it - your goal is still to become Superman.”

Recommendations for government and society

The professor recommended that the government should accept the most attractive funding proposals to increase investment in R&D and empower the participation of private institutions.

For society, Hausmann stressed the need to rethink Mexico in an AI context, thereby improving education, health, security, and production.

The Harvard professor recognized Tecnológico de Monterrey’s role in this:

“I don’t believe there’s a university in Latin America better prepared to unite the university and business worlds and solve the ‘chicken and egg problem’ of innovation.”

70th anniversary of the Bachelor’s Degree in Economics

The participation of Ricardo Hausmann, Director of Harvard’s Center for International Development, was part of the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Bachelor’s Degree in Economics (LEC) at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

This event was held on Monterrey campus on October 3 and 4 and comprised lectures, panels, workshops, and historical tours of the campus.

Prominent academics such as Juan Pablo Murra, Rector of the Tec, and leaders like Tec graduate Carlos Salazar Lomelín, Edna Jaime, and Elvira Naranjo recognized the impact this degree had made on the training of professionals who have made contributions throughout the country.

During this celebration, topics such as international economics, gender, public policy, financial markets, innovation, digital economy, and climate change were also addressed by experts such as María de Lourdes Dieck-Assad, Eva Arceo, Miguel Talamas, and Gabriel Yorio.

There were also workshops on behavioral economics, data science, and artificial intelligence, as well as tours showing the evolution of the degree since its inception.

ALSO READ: